By now, we are sure you have heard someone in the financial industry declare that, “interest rates are rising.” We believe the proper response to that statement should be: What interest rates are rising?

In the fixed income world, the two most common reference points for interest rates are (1) the federal funds rate, and (2) US treasury rates (more specifically, the 10-year Treasury). However, these two data points rates are not as related as one may think.

The federal funds rate is the interest rate that member banks of the Federal Reserve charge each other for overnight loans. It is a critical part of our economic and banking system. When you hear about the Federal Reserve raising interest rates, it is adjusting rates on these overnight loans.

So why does the Federal Reserve raise the federal funds rate?

The Federal Reserve has a dual policy mandate: price stability (control inflation) and maximum employment. The Fed adjusts the federal funds rate in an effort to accomplish these goals. Lower rates are intended to stimulate the economy as borrowing costs decrease, while higher rates are intended to slow down (tighten) the economy as borrowing costs increase.

Past Federal Reserve Chairs adjusted the federal funds rate to assist in accomplishing their policy goals. Chair Paul Volcker aggressively raised rates in the 1980s to battle stagflation (high unemployment, high inflation and slow growth) which ultimately plunged the US economy into a recession. Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke raised rates 17 consecutive times prior to the Great Recession. Janet Yellen’s 25 basis point rate hike in December 2015 was the Fed’s first since 2006 and came after 7 years of unprecedented Quantitative Easing (QE) and Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP).

Adjusting the federal funds rate is meant to serve as a guide for market participants. Markets keenly follow changes to the federal funds rate as they are the manifestation of the Fed’s views on economic growth, employment and price inflation. As mentioned above, Janet Yellen ended the Fed’s ZIRP and raised rates for the first time in December 2015. As we sit here on March 29th, the Fed has raised their target rate 6 times in this tightening cycle, from 0%-0.25% to 1.5%-1.75%.

The Fed raising the federal funds interest rate has no direct effect on US treasury rates. Why?

Since the fed funds rate concerns just overnight loans, the Federal Reserve’s actions are most profoundly felt on the short-end of the yield curve. If the Fed raises its overnight rate, it follows that short-term bond interest rates should also rise (while their prices fall).

Rates on longer-term Treasury bonds (such as the 10-year US Treasury, the most common benchmark when discussing treasury rates) are less affected by changes in the Fed’s overnight funds rate. The longer dated Treasury bonds are more impacted by traders and their assessments on future economic growth and inflation.

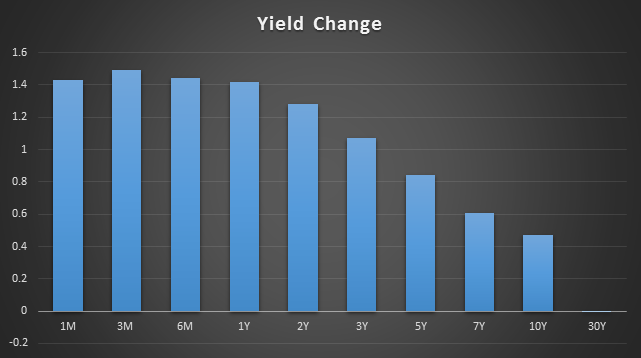

Since December 2015, while the Fed has continued on a path of raising short term rates, inconsistent inflation data and conservative growth prospects have kept a lid on longer dated bond yields. The difference in yield changes across the treasury curve since the Fed started raising rates is reflected in the chart below.

Short-term yields (1-3-6 month and 1-2 year) have risen over 125 basis points (1.25%), which is right in line with the Fed’s actions. However, longer-term yields (10-30 year) have not experienced the same movement, and specifically, 30-year Treasury yields have barely budged.

This is why, when managing our in-house fixed income strategies, we position client portfolios around the intermediate part of the curve (5-10 years). We have chosen to avoid the damage done to short-term bond prices as a result of the Fed’s actions. Therefore, when the Fed announces that it is raising interest rates, it does not mean that the bonds in our portfolios are negatively affected.

What does this difference in the relative changes in interest rates between short-term and long-term bonds mean for the stock market and the economy?

If the current track continues – where short-term rates are rising faster than long-term rates – you eventually arrive at an inverted yield curve. Many economists believe that an inverted yield curve, where the 2-year treasury rate (short-term) is higher than the 10-year treasury (longer-term), is a precursor to a recession. While economic growth is currently positive, and a recession does not appear to be on the horizon, we closely monitor the “spread” between “2s” and “10s” because after decreasing significantly in 2017, it is at the lowest levels since the last recession.

This process, known as yield curve flattening, highlights a lack of symmetry between Fed actions and investor sentiment regarding growth and inflation expectations. This is not to say that the Fed is wrong in its assessments. It is simply to say that monetary tightening – making it more expensive to borrow and potentially slowing economic growth – in an environment where the US economy is struggling to maintain 2% economic growth is causing a tug-of-war between short-term and long-term rates.

To further highlight this asymmetry, the chart below shows the Federal Funds target rate lower bound (white line) versus the 10-year treasury (orange line) since the Fed started raising rates in 2015.

After the first interest rate increase in December 2015, the 10-year US treasury yield actually went down. The 10-year yield dropped to an all-time low in July 2016, a decline of almost 100 basis points (1.0%) from the 2.29% level at the time the Fed started “raising rates.” Rates remained low until the 2016 US Presidential election unleashed euphoria created by campaign promises for pro-growth policies and rates moved sharply higher.

Further, an aggressive Fed hiked the fed funds rate 3 times in 2017, yet there was just a 0.04% increase in the 10-year treasury.

It is impossible to ignore the possibility for higher interest rates in the future. This is the exact reason we believe strongly in investing in high coupon, individual municipal bonds which not only behave similarly to treasuries, but also offer significantly more yield on a tax-equivalent basis. Regardless of where rates go, investors know they will receive their principal investment of $100 back at the maturity/call date.

In sum, just because you hear “interest rates are rising”, it does not mean the bonds in your portfolio must be negatively affected.

To learn more about how we can provide value to you and your clients, you can visit us at www.macroviewim.com or call 301-907-6795.

Disclosure: Nothing on this site should ever be considered to be advice, research or an invitation to buy or sell any securities. Full disclaimer.